Researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have invented an emergency ventilator that could help save the lives of patients suffering from COVID-19, the disease caused by novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.

Using standard parts that cost less than $400, the ventilator could be an affordable option when more sophisticated technology is not available, in short supply or too expensive.

“We wanted to build the simplest device that could be effective,” said Martin Breidenbach, professor emeritus of particle physics and astrophysics at SLAC and Stanford University, who led the project and hosted the initial studies in his home workshop. “Our acute shortage ventilator is exactly that, and we now want to get it into use as quickly as possible.”

While SLAC and Stanford do not produce or distribute this ventilator, they are offering the technology at no cost to others who want to build the ventilator and deploy it after having obtained regulatory approvals. The scientists described the device in a recent paper posted to the medRxiv preprint server.

A fancy version of the simplest technology

Ventilators provide air to patients who can’t breathe sufficiently on their own – a common problem for those severely affected by COVID-19.

A ventilator’s operating principle is simple: It compresses oxygen-rich air and pushes it through tubes into a patient’s lungs, expanding them and helping the patient take up oxygen. The lungs contract on their own, pushing the air back out. Then the cycle starts over.

In the simplest version, doctors squeeze a self-inflating bag by hand to pump air into the lungs. High-end automated versions compress the air in other ways and use complex electronics to control pressure, volume, air flow and other parameters.

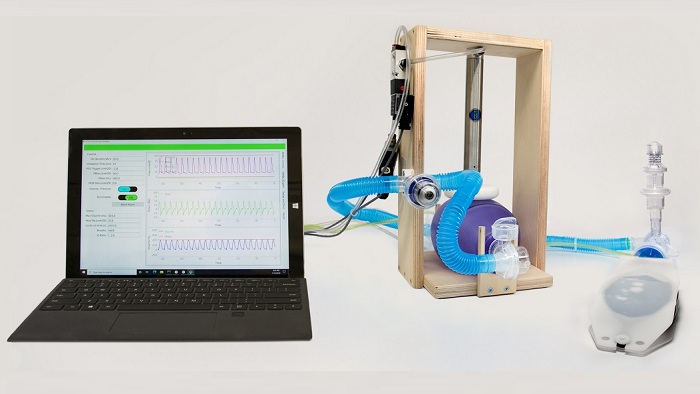

SLAC’s emergency ventilator is based on a simple model, but it adds a mechanism that automatically squeezes the self-inflating bag. The system also incorporates modern, inexpensive electronic pressure sensors and microcomputers with sophisticated software that precisely controls the squeeze. The microcomputers also drive a small control panel, and operators can control the system with that or with a laptop computer. The rest is standard hospital parts.

Other groups have developed emergency ventilators in recent months, often by simplifying fancier machines. “Our invention stands out for the opposite approach: We made a fancier version of the simplest ventilator design,” said SLAC project scientist Christina Ignarra, who helped build the device.

The simple design allowed the team to develop, build and test the device in about four months. It also made the ventilator very inexpensive – less than $400 per unit, compared to $20,000 or more for a professional-grade system with field support.

“These qualities should make the ventilator particularly helpful for mid- and low-income countries, where medical resources are scarce,” said Michael Bressack, a Bay Area pediatrician and ICU doctor, who has been on several medical missions in Asia, Africa and South America.

A team of physicists and doctors

Bressack actually started the project. In March, he had just returned from a mission in Bangladesh when COVID-19 hospitalizations were skyrocketing in New York and potential shortages of life-saving ventilators were a big concern. He started talking to his physicist friend, Breidenbach, to see if scientists and engineers at SLAC could lend their technical expertise to develop an affordable emergency solution.

The project quickly took off. Bressack pulled in respiratory therapists and ventilator experts, and Breidenbach brought in several of his colleagues, including Dan Akerib and Tom Shutt, co-leaders of the lab’s contributions to the LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) dark matter experiment.

SLAC’s acute shortage ventilator project started in the home workshop of Martin Breidenbach, professor emeritus of particle physics and astrophysics at SLAC and Stanford. (Jacqueline Orrell/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory)

Ignarra, who also works on LZ, said, “We quickly realized that the project was right up our alley. In our experiment, we work with tubes and valves to carefully control the flow of high-purity gases. So, in a way, building a ventilator was not that much different. And it was extremely gratifying to jump in and do something that might directly help in the coronavirus situation.”

To jumpstart the project without lab access due to the Bay Area’s shelter-in-place order, Breidenbach began building several prototypes in his home workshop. He used materials around the shop, ventilator parts bought out of pocket from high-tech distributors, and other components dropped off by team members at his home. He tested what he had built with a Michigan Instruments Lung Simulator that simulates the behavior of sick and healthy human lungs. With additional support from the DOE and Stanford, the project quickly expanded and the team set up four more prototypes at SLAC once the scientists were allowed to go back to the lab.

They also took the ventilator to the VA Palo Alto Health Care System for more advanced tests. In particular, they wanted to make sure their device fulfilled requirements from the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation for simplified ventilator designs.

SLAC’s acute shortage ventilator is tested at the VA Palo Alto Health Care System. (Sander Breur/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory)

Available at no cost

The tests were successful, and the team is now giving their invention away for free. This is about saving lives, not about making money, they said.

“We’re soliciting proposals from companies that are willing to take the technology beyond the lab and deploy it in the field,” said Evan Elder from Stanford’s Office of Technology Licensing (OTL), who is helping with getting the word out. “When we find corporate partners that are a good fit, we’ll be offering royalty-free licenses for at least a year.” Based on the state of the pandemic, this approach will then be reevaluated.

Part of the project was supported by the DOE Office of Science through the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, a consortium of DOE national laboratories focused on response to COVID-19, with funding provided by the Coronavirus CARES Act.