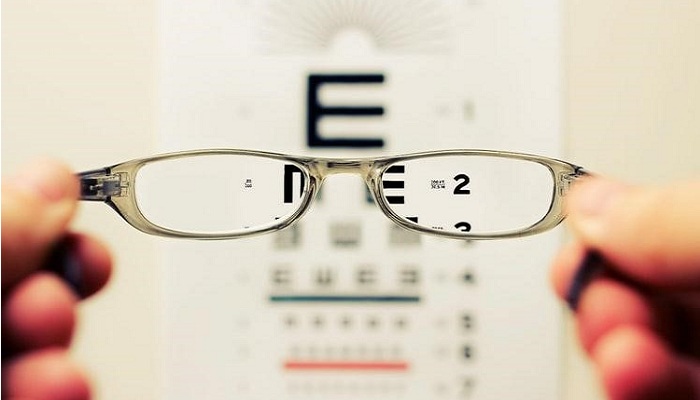

Globally, over one billion people — including workers and schoolchildren — strain to see the world around them.

Uncorrected vision is a major yet under-funded global health problem. It is an international development problem, too. The World Health Organization has estimated that uncorrected and under-corrected vision costs the international economy more than $200 billion annually in lost productivity, with much of this loss concentrated in low- and middle-income countries.

“People who do not have access to eye care are prevented from achieving their potential and this is also a major barrier to economic and human progress globally,” said Jennifer Hyde, Executive Director of GoodVision USA. “In fact, we can help solve this international crisis with simple pairs of eyeglasses that can be produced and distributed for very low cost.”

GoodVision introduced the world’s smallest eyeglass making factory almost 10 years ago — a suitcase sized system that requires no electricity, allowing the glasses to be made on-site with a material cost of around one dollar. The glasses retail for only a few dollars and are free for students. This innovative, sustainable system assists those who do not have access to vision care in some of the most remote communities in the world.

Low- and middle-income countries often lack the human resources and health system capacity to provide quality eye care for their population. Liberia, for one, has fewer than 50 eye doctors and vision technicians for a nation of 4 million people. GoodVision’s unique system of making affordable glasses utilizes a social business model, training local staff as vision technicians. This model not only improves sight but also contributes to economic development through job

creation.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, GoodVision has continued to provide safe job training, vision screening and free or low-cost eyeglasses. This is terrific news for students like Philipmena, a tenth grader in Monrovia, Liberia who once struggled to make out the words on the chalkboard.

Last year a GoodVision team arrived at her school, screened Philipmena and her classmates for vision problems, and gave her a pair of eyeglasses. Today Philipmena dreams of becoming a medical doctor.

The project in Liberia project saw almost 20 new GoodVision Technicians trained in early 2021. These technicians are now delivering optical and eye care throughout the country. “Over the next two years we are poised to help 30,000 Liberians, like Philipmena, to reach their potential,”

Hyde said.