Thanks to recent developments made by a team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, getting an ultrasound may soon be as simple as applying a Band-Aid. A novel bio-adhesive ultrasound device, or ultrasound sticker, has been created by researchers that can record 48 hours’ worth of ultrasound images of organs, muscles, and tissues. The sticker will eventually be usable at home, benefiting everyone but being especially helpful for caring for athletes and pregnant women.

Conventional ultrasound technology can only be found in hospitals, needs big, heavy equipment, and produces photos after a single, quick session. Now, a tiny, wearable patch that uses the same technology might be available.

According to Xuanhe Zhao, PhD, a member of the MIT team and senior author of the new Science paper describing the gadget, it will be a real game-changer in the medical imaging domain, notably ultrasonic imaging and the field of wearable electronics.

A View Inside

Traditional ultrasound imaging begins with the application of a gel to the skin to aid in the transmission of ultrasonic waves. A stick-like probe that is pushed into the appropriate location generates these waves. The waves are reflected by the body’s interior organs, and when they return to the probe and are picked up, they produce an image.

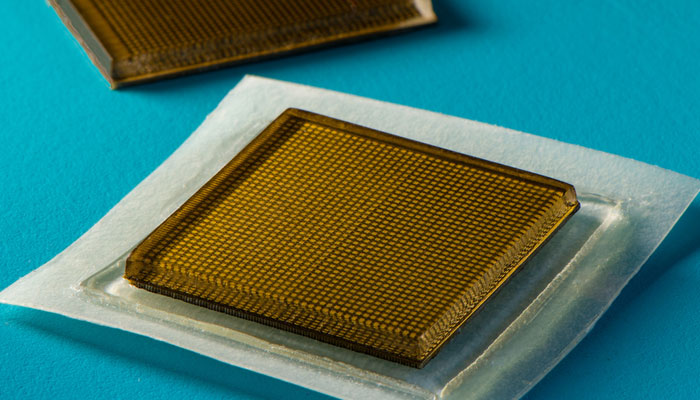

Zhao and his team developed a thin patch probe that works with a couplant that resembles Jell-O to transfer ultrasonic waves rather than just gel and a stick. The sticker is approximately the size and thickness of a nickel, measuring 2 centimetres square and 2 to 3 millimetres thick. The patch enables imaging up to 20 centimetres below the surface as well as near the surface.

Staying With You

Testing of the sticker on 15 people in various body regions, such as the arms, neck, and chest, revealed just a few of the potential advantages. Over the course of 48 hours, participants were watched as they went about their daily lives by walking, running, and riding bicycles.

The ultrasound sticker, for instance, was able to continually photograph the biceps for 48 hours when placed on the arm. Zhao was able to track the microdamage in these muscles before and after a one-hour weightlifting session thanks to their sensitivity. Zhao thinks that in the future, the ultrasound sticker will warn you when the activity is sufficient, maybe combining it with some image processing algorithm, which could aid with injury prevention or rehab.

The sticker could check blood pressure when worn around the neck (BP). According to Zhao, it is challenging to create a wearable, dependable, and long-lasting BP measurement. This device might continuously check the carotid artery’s diameter and alert people and medical professionals to high blood pressure.

The device offered prospective new treatment options for people with cardiac problems when it was placed on the chest. According to Zhao, the ultrasound can be used directly on the chest and can give clinicians pictures or videos.

The capability to monitor foetuses is another aspect that was not tested in the research that Zhao believes has potential. Pregnant women typically undergo two to three ultrasounds. The ultrasound sticker might make it possible for a mother and her doctor to check on the health of the foetus as frequently as necessary.

Future Steps

Currently, cables are used to link the sticker to a data box. In order to connect to the user’s smartphone, Zhao and his team are developing a second-generation wireless sticker. He predicts that it will take between two and five years for the integrated system to go wireless and gain FDA clearance for usage in American hospitals.

He believes that this is just the beginning of a significant advancement in wearable technology that will eventually lead to improved health for the whole planet.